Everything in life is difficult if you make it that way. That doesn’t mean that everything in life can be made easy but for the most part it can be made manageable. They don’t teach you that in school. Orthodontic residency is a losing clinical battle against outliers. That is to say, residents are encouraged to offer consumers unrealistic or undesirable treatment goals and taught to use inefficient, ineffective mechanical systems and inappropriate clinical decision-making that routinely fails to deliver the desired outcome. This can set the resident up for a career of self-doubt and feelings of inadequacy. Dull knives don’t help much in a gun fight. I call this the Set-Up-To-Fail Syndrome.

Variation in teeth and jaws is the rule not the exception. So why would we think that we can achieve the same goal for every case? Or why would we want the same goal for every case? Because that was what we were taught. All cases should be finished to Angle’s definition of “ideal occlusion”. To achieve this outcome for every case may require incorporation of tooth extraction, prosthetic dentistry and/or jaw surgery into the plan of service. However, not all consumers will accept the “required” treatment modalities for attainment of this supposed ideal. Most consumers don’t want what we think is their imagined ideal. Over time, all orthodontists experience a disconnect between orthodontic theory and their own orthodontic practice experience resulting in the Difficult Orthodontic Case (DOC) mental model.

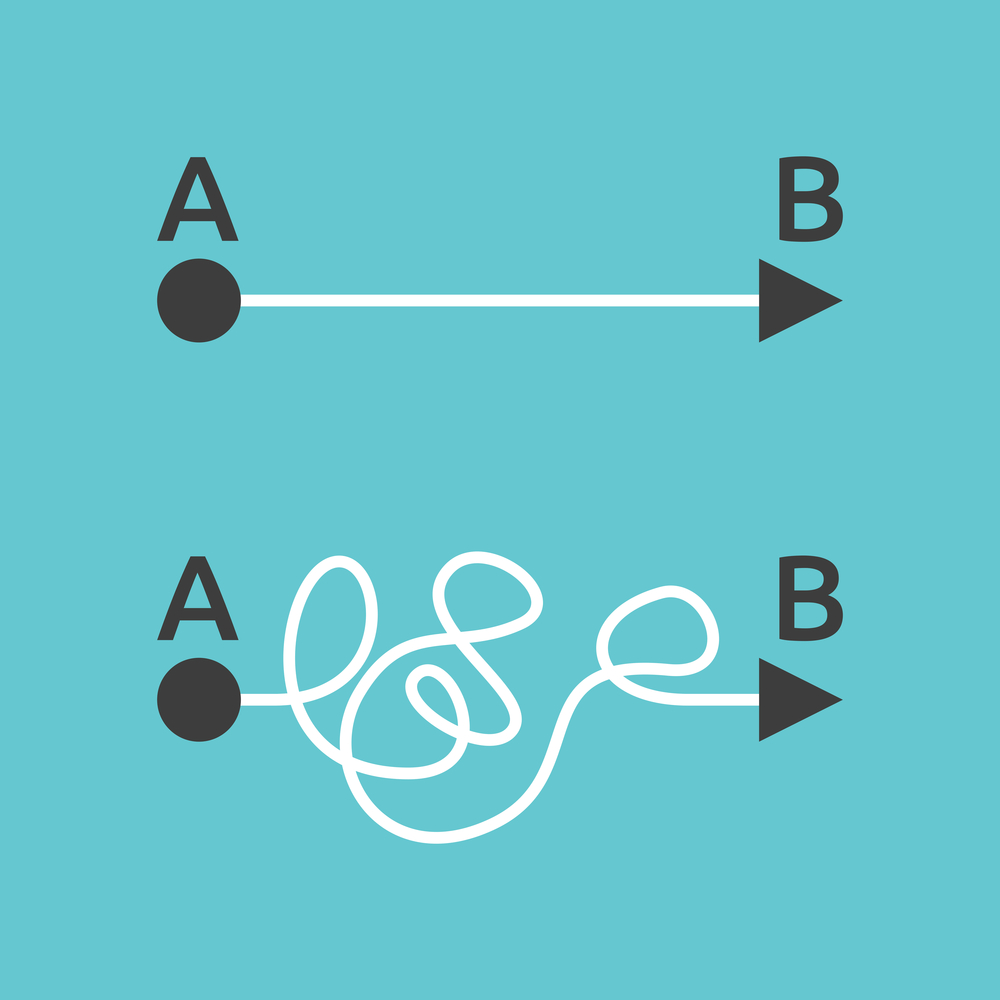

The DOC mental model is a self-protective mechanism that obscures an orthodontist’s ability to see that the likelihood of their treatment plan actually achieving their desired outcome is exceedingly low. With the “ideal” in mind, many of us at one point or another have fallen into the trap of creating long and complicated treatment plans that utilize screws, hole punchers, and vibrators with the hope of achieving the improbable. By labelling a case “difficult”, the orthodontist is able to:

- Safeguard themselves from guilt or blame when the case ends up sideways

- Boost their self-confidence and ego when the improbable is actually achieved

- Prevent the consumer from purchasing low “quality” orthodontics, e.g-anything less than what they believe is required to treat the case

What if I told you that there is no such thing as a difficult case? There are surely difficult consumers (kids, parents, adults) but these challenges are in the realm of interpersonal skills and not anatomic features. Every orthodontic condition is manageable when the consumer is aware of what their options are and what is needed to fulfill any or all of their expectations of treatment. If the consumer is not willing to undergo measures necessary to achieve all of their goals, tell them! In that case, treatment should be focused on improvement versus normalization. In other words, straighter versus straight.

Each time you decide to start a case or not, it is a strategic business decision. If your proposed plan’s therapeutic return on consumer investment doesn’t look promising, don’t do it. If it does, by all means start the same day! With this mindset, you won’t think about terms like easy or difficult but rather you’ll think about terms like appropriate vs inappropriate, realistic vs heroic and profitable vs unprofitable.

Marc Ackerman, DMD, MBA